Glossary: Banmal

by girlfriday

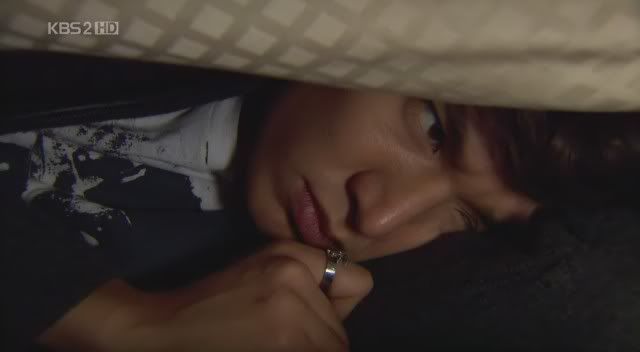

While Eun-jo never called Ki-hoon “oppa,” she certainly used her share of banmal with him

One of the things I find endlessly fascinating about the Korean language is the magnitude of what people call each other, and how they address one another as relationships evolve. As javabeans noted, in romantic comedies, we often squee equally over kisses as we do over the first time characters use banmal with each other. So what is banmal, and what are the rules? How can banmal be rude in one moment, and romantic in the next? Who gets to use banmal, and why is it meaningful when characters switch from jondae to banmal?

Banmal is informal or familiar speech, and the literal word can be translated as: “half” and “word/speech.” It’s half-speak, or jondae cut in half. It’s not so much the volume of words that’s cut, although banmal does require fewer words to convey meaning. It’s the formality and the extraneous polite address that can be pared down when using banmal.

As a general rule, people who are: 1) of the same age or older than you, and 2) familiar with you can use banmal.

The clearest delineations are within families. Anyone who’s older than you in your family will use banmal with you. The reverse is a little trickier. If you’re the younger person, when can you use banmal?

Within immediate families, siblings use banmal with each other. Some people who are more distant with their parents use jondae, while most close families use banmal with parents. I speak to my parents in banmal and will continue to do so my whole life. There is also a generational difference, because while I use banmal with my parents, they use jondae with their parents.

But there’s no hard and fast rule, even with family members, because banmal is used only when you feel that level of comfort with someone. For example, in Cinderella’s Sister, Ki-hoon uses jondae with Ki-jung, although they are brothers. In Coffee Prince, Eun-chan uses banmal with her mom, since they are very close. (This is common in most mother-daughter relationships and is, for instance, far more common than the use of banmal between father and son.)

The family rules can be applied to any sort of external group as well. Think: crime families, groups of mixed-aged friends at a university, a team of co-workers. Naturally, anyone who is older or in a position of authority (the hyung-nim, the sunbae, the boss) will use banmal, while everyone else will speak in jondae.

In Pasta, Yoo-kyung uses banmal with Hyun-wook, thinking he’s the new kid, below her on the totem pole. This assumption, regardless of age, allows her the freedom to use banmal. That is, until the next day, when Hyun-wook is introduced as the new Head Chef, at which point the roles are reversed. Chef now uses banmal, while Yoo-kyung switches to jondae.

When you’re a kid, things are simple: you use jondae with adults, and banmal with other kids. As an adult, banmal is used only with people you are familiar with, having already established that you are on banmal terms. You would never start out an interaction using banmal. Not cool.

So how on earth do you establish banmal terms? Cutting down to banmal requires a tacit agreement to do so, by both parties. Usually there is a conversation, or one person does so experimentally, seeking approval to speak comfortably. The general rule is, you must get permission to do so. Once jondae is cut, there’s no need to go back.

For example, in Coffee Prince, Eun-chan has only met Han-seong a few times, so they still speak to each other in jondae. But when they get friendlier and she finds out that he’s 31 versus her 24, she tells him to “lower his words,” which he does immediately. This is an example of the most common way to get to banmal.

If you are identified as older, you have more freedom to cut your words. Han-kyul, in contrast, uses banmal right away with Eun-chan because a) he thinks she’s a dude, and b) he thinks she’s a punk kid on top of it all. Here again, gender relations come into play, because note that Han-seong starts out using jondae despite the age difference because Eun-chan is a girl. Whereas Han-kyul uses banmal comfortably, thinking that Eun-chan is a guy.

Now, in a romantic relationship, these differences take on more significant meanings. Whether or not a couple uses banmal with each other speaks volumes about where they are emotionally, and how comfortable they feel around each other. If one party is older, then the older one may drop the formalities as a sign of closeness. And very commonly, men will cut to banmal first.

In more traditional couples, men/husbands use banmal while women/wives use jondae. I know. Don’t hate mail me. I didn’t invent it. Personally, I think it should be all or nothing, and none of this in-between stuff, especially if you’re married. But this is still the dominant practice in traditional couples, as being the man or head of the household gives one an elevated status in a patriarchal society. It’s not so much that doing it one way or the other is right or wrong; here it’s a matter of choice, and it reveals what sort of dynamic is in play within the couple.

But the reverse is true too, in that a girl’s got some power in how she chooses to wield jondae/banmal. In Boys Before Flowers, Jandi uses jondae with Ji-hoo sunbae and the rest of F4, indicating respect (since they are older). But she refuses to give Gu Jun-pyo any respect, because she finds him hateful. She therefore strictly uses banmal with him, which is frustrating to Jun-pyo, who is used to the entire world kissing his feet and cowering in his presence.

Similarly, in Cinderella’s Sister, Eun-jo uses banmal with Ki-hoon in a deliberately disrespectful way. It’s different from Hyo-sun’s use of banmal, since she always calls him oppa. But we all know Eun-jo would rather die, so she speaks in banmal knowing that she’s overstepping her bounds.

Using banmal goes hand in hand with how people address each other. If a couple is roughly the same age, they will start out calling each other name-sshi and speaking in jondae. Once you get to banmal, name-sshi becomes name-ah or name-ya (which are both equivalent and based on consonant/vowel, just like “a tree,” “an apple”; eg. Eun-jo-ya, Ki-hoon-ah).

Here’s the main difference between jondae and banmal: there’s no way to say “YOU” in jondae. Only in banmal. Jondae is built structurally so that you cannot address an elder directly in the second person. So even when you are speaking to your teacher directly, you will be saying something like, “I will give the assignment to Teacher,” or to your mom: “Mom doesn’t get me.” It’s weird in English, (which is why this difference is lost in translation) but the distance is built into the language on purpose in jondae. Titles, like “Mom” will always keep that distance in speech, no matter if you use banmal.

But with friends, colleagues, significant others—anyone you call by name, once you cut to banmal, you can say the equivalent of “you,” so that you can speak to each other without the third-person address. So you could say to your friend: “You suck.” No titles, no frills, no referring to each other in the third person.

This may seem like a small change, but it’s a world of difference in personal interaction. Imagine if Ki-hoon continued to use jondae, as he does when he first returns after his eight-year absence: “Eun-jo-sshi is awful.” It’s a totally different feeling from the very direct: “You awful girl.”

Think of it this way too: “I love Ki-hoon-sshi,” vs. “I love you, you silent, noble idiot!” Okay, that last part was editorialized, but you catch my drift. There are middle ground ways around this, of course, like the use of endearments + jondae, or opting out of direct address, but this is the basic structure of jondae/banmal.

The colloquial words Koreans use in order to cut formality reveal a lot about their feelings towards jondae vs. banmal: “drop, lower, cut, peel, pare, strip, subtract, reduce, ease, relieve, release, let go, set free, liberate.”

The most common phrase used when suggesting banmal is to “speak comfortably” or “plainly.” There’s a reason—using banmal actually frees up your speech. There are just things that are impossibly difficult to express when speaking in jondae. It’s a cultural perspective, to be sure, that jondaemal feels restrictive and formal, and that it creates a distance between speakers.

Conversely, using banmal actually makes people feel comfortable—it puts speakers at ease, because by cutting formalities in speech, you’re actually agreeing to be more open, free, and say whatever you please. It’s like a social contract, that if we’re in a banmal-kind of relationship, we’re cool to say what we really think. Of course it also says to the world that we’re close.

Which is why it’s a significant milestone in the drama couple’s journey. Even if it forces you to endure someone dissing you for the first time ever. That’s right, Gu Jun-pyo. I’m talking to you.

RELATED POSTS

Tags: Boys Before Flowers, Cinderella's Sister, Coffee Prince, Pasta

Interview with Kim Yoo-jung

Interview with Kim Yoo-jung Hello Dramabeans series

Hello Dramabeans series

![[2022 Year in Review] The Bean Count](https://www.dramabeans.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/beancount_2022.png)

Required fields are marked *

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

101 GODDESS

November 18, 2013 at 4:34 AM

CONFUSING...AM I THE ONLY ONE????

Required fields are marked *

102 Helenya

November 30, 2014 at 7:03 PM

I wish subbers would colour code when jondaemal and banmal used, so non-Korean speakers could see when it's been used inappropriately. I missed the whole Jandi - Jun pyo dynamic in BBF

Required fields are marked *

Iamastonished

November 26, 2016 at 10:14 AM

Great idea! I really wish I spoke Korean. One issue I have with formal and informal speech is, doesn't show rudeness on the part of the formal speaker when it is in opposition to the emotional aspect of the relationship such as the relationship between man and wife. Isn't the patriarchal language construction a stumbling block to honest communication between the sexes? Isn't it difficult for women to value their own thought process when the language is biased toward the male point of view? I seems so servile. I am not judging but is that why so many female protagonist dress in drag to get on with their lives and explore the world in so many dramas. I think that Korean cinema is sadly overlooked at the Cannes film festival awards. Maybe The language banal/jondaemal translation issue is part of the reason that the fine content is misunderstood and overlooked. That being said, the acting and the cinematography is so evident they should have a clue. Not that I am not interested in Kpop, it is fascinating but please produce a list of the finest films and dramas for the geekiest film buffs. You know the subtleties of the language and must have a deeper understanding of the quality of the scripts.

Required fields are marked *

103 Iamastonished

November 26, 2016 at 9:04 AM

Just wondering, do Korean people think that English speakers are inferior or rude because there is not much formality in English address?

Required fields are marked *